|

I was forced to read Huckleberry Finn in high school for one of my English classes. I had become a good reader through a point system implemented in early elementary school. They had books we could take from a shelf that were worth 1 to 5 points and if you read them, you got to take a test on them, and if you answered most of the questions right, then you were awarded the points. Through a process of “buzzsawing” where I read as quickly as I could through the 1 and 2 point books, and took the tests for them, I quickly wound up with the most points of my class.

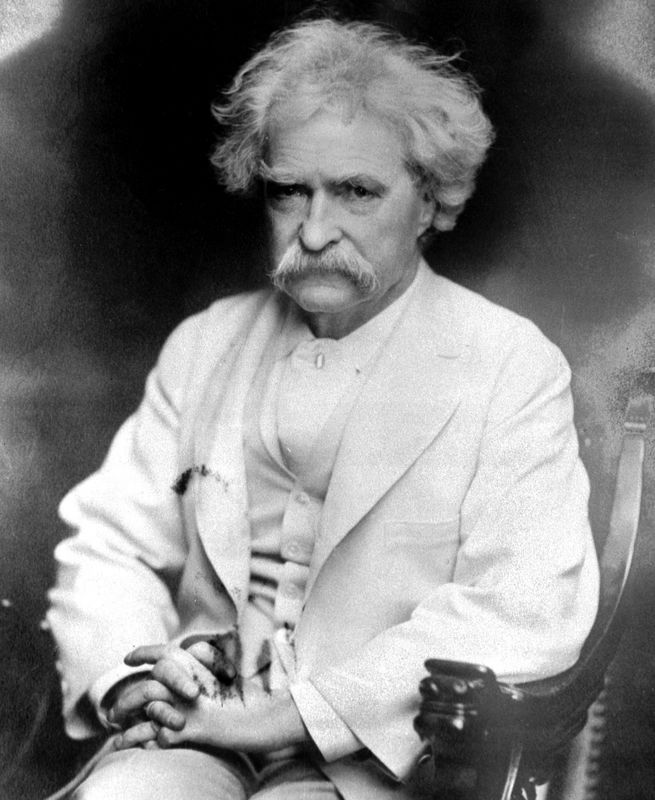

I did not look forward to this book by Mark Twain because the books I had been forced to read were terrible. Perhaps the stand-out book in my mind would be The Old Man and The Sea by Ernest Hemmingway. Even the title of that book is enough to elicit a sharp yawn. In fact, up until I read Huck Finn, I was absolutely sure that my path would not be English at all. But I read it, and it hit hard. The vernacular couldn’t be understood unless read out loud. The characters were charming and exhibited a kind of low-life wit. The word “nigger” was used upwards of 200 times. Hamlet’s famous soliloquy gets butchered. A family gets in a dustup with another family over something both of them forgot long ago. Huck fakes his death. This was definitely my kind of book.

I read through it ravenously, and then read through it again just to make sure I picked everything up (I didn’t). I even got a sweet edition of it with explanatory notes, a glossary, and maps at the end. There was no way I was going to let go of the book’s brilliance. I even went out and found Mark Twain’s other books and read them, too. It’s not strange that his works began to show a distinctly darker tone after this stunningly mature piece. With A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger, Twain would look into an unyielding abyss from which he would never return.

The river was Mark Twain’s favorite subject. A traveling man, Mark Twain wrote about and found no greater pleasure than those of the river. It’s no wonder that what is perhaps his greatest book is all about the river (and I’m talking about the Mississippi here). It’s also clear that he knew what would turn out to be his best book as it took 5 years to complete and he actually completed four other books in the process including Life On The Mississippi which not only functions as a discussion of his experience on the river as a steamboat captain, but also most likely prepared Twain himself for the writing of his magnum opus.

The river was home for Twain, and naturally he felt most comfortable in that habitat. Perhaps his discomfort outside the river could be seen in his next book, A Yankee. It’s perhaps telling that he doesn’t take the river at all in this book, but crosses the entire Atlantic as his hero gets transported all the way to medieval England. Even if this work is heavily contrived, I would count this as a close second to Huckleberry Finn in the masterpiece department. The book is savagely funny at parts and poignantly heartbreaking at others. Perhaps Twain knew he was in uncomfortable territory as his climax and denouement are about as chilling as Twain would ever get. Perhaps the ocean into which he would set sail swallowed him up at that moment and kept him within its clutches to the very end with his final work, No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger, which has been said to be his most unrelentingly dark piece of work. It’s true that Twain never threw away his humor up until this magnificent and strange piece- after all, he was still able to write a Pudd’nhead Wilson and a couple of new Tom Sawyer adventures, Tom Sawyer Abroad and Tom Sawyer, Detective, both appropriately narrated by Huck Finn.

But the damage had been done. The mark of Yankee stayed with Pudd’nhead Wilson, labeled a tragedy after its title character hijacked the story from Those Extraordinary Twins- the original title. Notable is the fact that Twain wrote his fair share of bad literature also. Tom Sawyer Abroad and Tom Sawyer, Detective (especially) have all the markings of your average pulp novel of the day. In fact, the latter of these so clearly plays off the dichotomy of Watson and Sherlock Holmes that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would have undoubtedly lifted an eyebrow. And let me tell you, Twain wrote this kind of stuff with vigor. Many of his works aren’t even in print any more, and I’m referring to a small bevy of plays in which he apparently put quite a bit of effort.

No comments:

Post a Comment